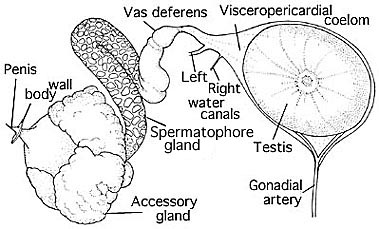

We have used Cirroctopus glacialis (Opisthoteuthidae) to illustrate the male reproductive tract of cirrates. The reduced visceropericardial coelom extends over the testis to two openings from which sperm pass from the testis into the coelom and then into the vas deferens. The latter joins the coelom at the same point as the water canal (only one water canal seemed to be present). The vas deferens opens into spermatophore gland I which has thick glandular walls and a rather large lumen. This gland connects with spermatophore gland II which appears to have an identical structure. The latter has a broad connection to the S-shaped spermatophore gland III. This gland has a very different appearance. The walls are thin with only a slight glandular component; most of the gland is lumen.

Figure. The male reproductive of Cirroctopus glacialis. Drawing by R. Young.

At the second curve in the gland a small glandular structure opens into the lumen. This is the "appendage to spermatophore gland III", in the terminology of Meyer (1906). The spermatophore gland III narrows into a duct that passes beneath Needham's sac. It opens into a common vestibule that is continuous with Needham's sac and the opening of the penial duct. Needham's sac sits atop the accessory glands and have thin but glandular walls and extensive lumina. In our specimen, the distal half of Needham's sac was collasped and not detectable externally, while the proximal portion rose well above accessory gland II. Accessory gland II showed no indication of having a bilobed structure other than a small dimple on the outer surface. Further along, the penial duct receives a large duct that apparently drains both accessory glands. The accessory glands consist of nearly a solid mass of glandular tissue and minimal lumina.

The penis projects freely into the mantle cavity as a dome that is little more than the end of accessory gland II.

Photographs of the male reproductive tract of Cirroctopus glacialis can be found here.

Terminology and homology

The male reproductive tract of many cirrates have been described. Especially important are papers by Meyer (1906), Ebersbach (1915) and Aldred et al. (1983). Since the male reproductive tract of cirrates is very different from that of incirrates, determining homologies between the two has been difficult and a different nomenclature has generally been applied which usually follows Meyer (1906). Ebersbach, however suggested that spermatophore glands I-III are homologous with the similar glands of other cephalopods. We can confirm this interpretation with two observations: (1) In most cephalopods this portion of the reproductive tract undergoes a coiling and uncoiling to form a complex S-shaped curve. We see this same coiling in Cirroctopus . (2) In Loligo, Drew (1911) refers to the first two components as Mucilaginous glands and the third as the Middle Tunic Gland. The mucilaginous glands form the secretions in which the spermatozoa are embedded and is the region where the sperm thread is spirally wound to form the sperm rope which is covered by a small amount of mucilaginous material. These glands have thick walls and an extensive cavity. The middle tunic gland comprises most of the next region and is thick walled, smooth, ciliated and with a prominent ridge. Here the ejaculatory apparatus is added followed by the middle tunic.

Spermatophores dissected out at this point are sticky and soft. We have examined fixed spermatophores from the third gland of Cirroctopus and from Needham's sac (left image in the photograph). They have a spirally coiled sperm rope and a thick soft gelatinous covering which is often distorted by the position in which they happened to be fixed. Aldred et al found similar spermatophores in this region in Cirrothauma murrayi (1983).

Figure. Left - Spermatophore of C. glacialis. Right - Sperm rope of the spermatophore that has been removed from its gelatinous covering. Photograph by R. Young.

Cirrates have no ejaculatory apparatus and the third gland has thin but glandular walls, a wide lumen and no ridge. Therefore, this is what we would expect to find if this region was homologous to the middle tunic gland. Ebersbach considered the "spermatophore reservoir" of Meyer (1906) to be the homologue of Needham's sac; we consider this a reasonable assumption. Apparently the hardening, or hardened coat is supplied by the accessory glands. The homologies of these glands are uncertain. Accessory gland II was unilobular in Cirroctopus but is bilobular in Opisthoteuthis depressa (Meyer, 1906) and the cirrates dissected by Ebersbach. The latter author preferred to label these lobes as accessory glands II and III. We prefer the terminology of Meyer (1906) which includes both lobes as accessory gland II. The accessory glands of Cirrothauma murrayi, seen in the drawing on the right, appear quite different from those of Cirroctopus and their number is uncertain (Aldred et al., 1983). Aldred et al. state that "On the dorsal side of the accessory gland is a thin walled diverticulum, also containing sperm packets ... ." This diverticulum is, apparently, the structure that we are calling Needham's sac (= seminal vesicle) in Cirroctopus. C. murrayi, unlike Cirroctopus, has both water canals.

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site